Article written by Dr Douglas Powell

As teenagers in the late 1970s – yes, I lived through disco — my friend Dave had a beat-up Ford Vega. Similar to the much-maligned Pinto, the Vega got us around for our teenage mischief, along with the green Datsun B-210 missing a front panel that I drove.

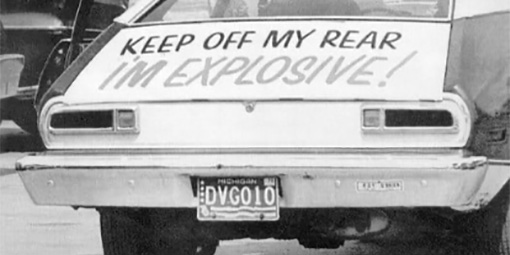

The Pinto became famous for its tendency to blow up when struck from behind, and also by the manufacturer’s claim that the Pinto met or exceeded all government standards. For over 40 years, the meet-government-standards line has been known to engender no trust and instead create distrust.

Watching the food industry is sometimes like watching the History Channel, a mix of fact, extraterrestrials and the perils of ignoring history.

In 2011, when ground beef with Salmonella Typhimurium sold by Hannaford’s sickened 19 people in seven states, the company spokesthingy said, “What I can tell you is all our record keeping practices either meet or exceed industry standards.”

Just like the Pinto.

Decades of risk communication research have shown in various fields that meeting government standards is about the worst thing you can say.

Especially when it involves groceries.

People who would think nothing of laying out $200 for a fancy-pants dinner and atmosphere, will digitally or electronically clip coupons to save $0.10.

I watch people when I go shopping for food, about every second day, and maybe they watch the creepy guy watching them.

My questions may not be the same as other cooks or parents, but I have a lot.

Should that bagged salad be re-washed? Some bags have labels and instructions, some don’t. What about the salad out in bins that came from pre-washed bags? Should it be re-washed?

Is washing strawberries or cantaloupe going to make them safer?

Where did those frozen berries come from? Am I really supposed to cook them and can’t have them in my yogurt because of a hepatitis A risk?

Are raw sprouts risky?

How long is that deli-meat good for? Is it safer at the counter or pre-packaged?

Should I use a thermometer or is piping hot a sufficient standard for cooking meat and frozen potpies? Can I tell if meat is cooked by using my tender fingertips?

Is that steak or roast beef mechanically tenderized and maybe requires a longer cook time or higher temperature?

Are those frozen chicken thingies made from raw or cooked product? Is it labeled? Is labeling an effective communication mechanism?

These are the questions I have as a food safety type and as a parent who has shopped for five daughters for a long time in multiple countries. It has guided much of our research.

I see lots of things wandering through the grocery store, but I don’t see much information about food safety.

When there is an outbreak, retailers rely on a go-to soundbite: “Food safety is our top priority.”

This sets up a mental incongruity: if food safety is your top priority, shouldn’t you show me?

The other common soundbite is, “We meet all government standards.” This is the Pinto defense – so named for the cars that met government standards but had a tendency to blow up when hit from behind – and is a neon sign to shop elsewhere.

Leaving brand protection to government inspectors or auditors is a bad idea.

For a while I started saying, rather than focus on training, which is never evaluated for effectiveness, change the food safety culture at supermarkets and elsewhere, and here’s how to do that.

But now the phrase, “We have a strong food safety culture,” is routinely rolled out but rarely understood, so I’m going back to my old line: show me what you do to keep people from barfing.

Food safety information needs to be rapid, reliable, relevant and repeated. I don’t see that at retail.

The days of assuming that all food at retail is safe are over. Some farmers, some companies, are better at food safety. And they should be rewarded.

Most of us just want to hang out with our kids and get some decent food – food that won’t make us barf.

Tying a brand or commodity – lettuce, tomatoes, meat — to the lowest common denominator of government inspections is a recipe for failure. The Pinto automobile also met government standards – didn’t help much in the court of public opinion.

The best growers, processors and retailers will far exceed minimal government standards, will proactively test to verify their food safety systems are working, will transparently publicise those results and will brag about their excellent food safety by marketing at retail so consumers can actually choose safe food.

Dr. Douglas Powell is a former professor of food safety who shops, cooks and ferments from his home in Brisbane, Australia.